Slaughter of farmed fish

As an industrial livestock sector, aquaculture has experienced rapid growth in recent decades. Today, almost as much farmed fish is consumed as wild fish.

Claudia Millán

Fish Welfare Specialist

22/03/2023

Today, aquaculture is an important source of aquatic food

Actually, if we include algae production, it exceeds world fisheries production. Regarding animals, the number of fish, molluscs and crustaceans reared on farms is similar to that from seas and oceans. For example, in 2020, global aquaculture production reached 87.5 million tons compared to 90.3 million tons from wild fisheries (FAO, 2022).

Most of these aquatic animals are destined for human consumption but do we know how they are slaughtered? So once they reach a commercial size, how are they slaughtered on farms? To answer these questions, we will compare how terrestrial and aquatic animals are slaughtered and explain the methods commonly used for farmed fish. We will also show which ones are aligned with animal welfare and review current laws and new standards of the leading certifications used in fish from aquaculture.

What happens in the case of terrestrial animals?

What standards apply when slaughtering pigs, chickens, and cows, for example? Easy answer: Council Regulation (EC) 1099/2009, specifying the design and conditions of slaughterhouses, training of slaughter personnel, pre- and post-slaughter veterinary inspections, mandatory stunning prior to slaughter, etc. This regulation aims to reduce any unnecessary stress suffered by animals, linking their welfare with food safety.

To understand it, the slaughter process for terrestrial animals is as follows. They are transported to the slaughterhouse, kept there briefly to rest after the journey and checked by veterinarians. After, they are moved to the slaughter area, stunned (so that they lose consciousness and do not suffer) and slaughtered. Throughout this complex stunning and slaughter process, problems can arise. This issue has led AWO to promote implementing a system of CCTV cameras in slaughterhouses to improve food chain control.

This European regulation details all the steps to be followed from animals arriving at the slaughterhouse until their slaughter, reducing the stress generated by slaughter as far as possible. So where is the problem? It does not fully protect fish. It only mentions that they should be spared unnecessary pain, distress or suffering. Another detail to remember is that fish are usually slaughtered on-farm without prior stunning, unlike terrestrial animals that are stunned and slaughtered in the slaughterhouse. Now, we leave rules aside (we will come back to them later) to explain the slaughter process.

How are farmed fish slaughtered?

Slaughter is divided into:

Fasting

Fish feeding is stopped when they reach commercial sizes. Fasting helps the digestive tract to be empty. By not eating, the animals need less energy to function, less oxygen to breathe and produce fewer faeces. Also, this process is done to reduce microbial contamination too. It must also consider the species' characteristics and the farm's environmental conditions. For example, high summer temperatures negatively affect fish welfare if fasting is prolonged longer than necessary.

Crowding

After fasting, fish are concentrated in an area of the tank (or cage) using nets to facilitate harvest. This stage causes them a lot of stress as there are many fishes in a small space from which they try to escape.

Harvest

It is the moment when fish are taken out of the tank (or cage) using a net or pumping system. Despite being effective, the net does not consider animal welfare. It causes the fish to be crushed dry (you can imagine what they suffer when removed from the water). On the other hand, the pumping system is more appropriate, although it must be designed so that fish do not suffer damage or stress when they come out.

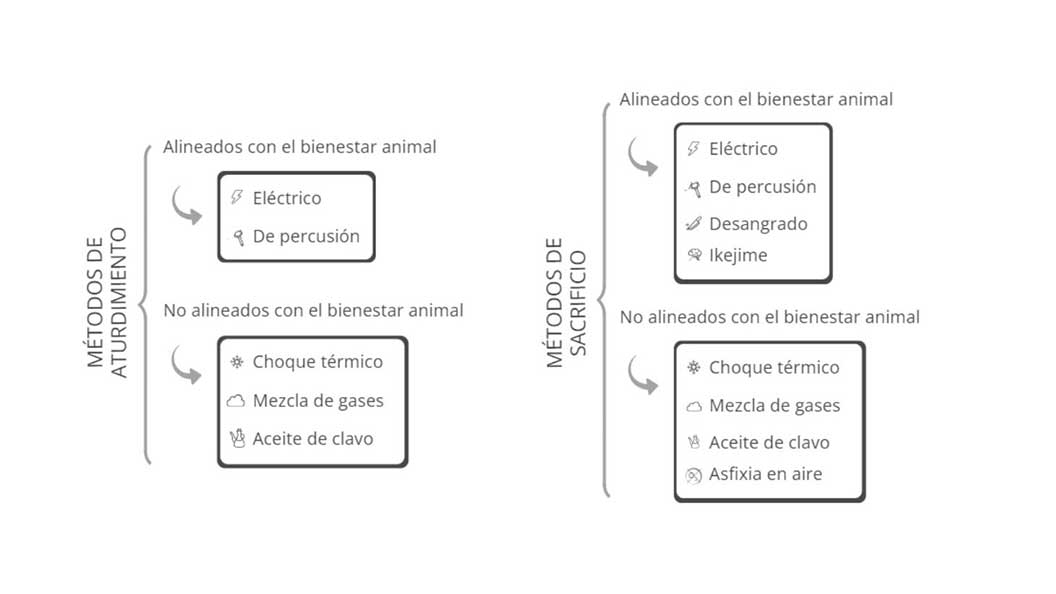

Stunning

Fish lose consciousness and sensibility quickly (1 second) without recovering them before slaughter, so their suffering is drastically reduced. For this reason, effective stunning before slaughter should be mandatory, although only some producing companies carry it out. Some methods are aligned with animal welfare (electric, percussion), while others are not (thermal shock, gas mixture).

Slaughter

Once slaughtered, fish is placed in containers with ice to preserve it during transportation to retailers, e.g., bars, catering, hotels, restaurants, and supermarkets. It should be noted that ice is often also used as a method of slaughter, apart from preserving animals’ products. It is considered a cruel slaughter because fish experience slow and agonising asphyxiation.

“It is essential to adjust the timing of each phase so as not to cause unnecessary pain or stress to the fish”

This is important because slaughter is already a long process that generates a lot of stress on animals, impacting fish's quality. In general, fish react to stress by producing lactic acid stored in their muscle, changing the flavour and texture of the fillet.

What are the methods aligned with animal welfare?

We start with stunning. The World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH) recognises electrical and percussive methods as the two options aligned with fish welfare. The former passes an electric current of sufficient strength through the brain. In the second one, stunning is caused by a sharp blow to the head given manually or with an object.

At the other extreme, there would be thermal shock, gas mixture and anaesthesia with clove oil. The first, known as ice asphyxiation, is the most frequent method in aquaculture in Southern Europe (Spain, Greece, and Italy) and other regions worldwide. Fish are placed in a container with a mixture of ice and water while waiting for them to die, experiencing pain and stress for several minutes. For example, different scientific studies show that it can take up to 20 minutes for sea bream and sea bass to lose consciousness.

Gas mixture (consisting mainly of carbon dioxide and nitrogen) and clove oil are still experimental. Diverse scientific groups are investigating the appropriate composition and dosage of the mixture to stun these animals effectively. Experiments have also been done to calculate the necessary dose of clove oil,generally used as an anaesthetic to reduce fish stress during handling. To summarise, using stunning methods aligned with animal welfare before slaughter is a step in the right direction.

Are they the same for slaughter?

Regarding slaughter methods, any stunning method can cause fish death if applied with sufficient force and for a prolonged time. For instance, long exposure to a mixture of ice and water, a high concentration of gases or clove oil, or an electric current strong enough will cause the animal's death. Apart from these, other slaughter methods used in aquaculture are air asphyxiation or exsanguination.

Air asphyxiation is similar to the one produced in ice but with the difference that fish are removed from the tank and left in a container where they die after a few minutes of intense agony. It is misaligned with animal welfare so its use is discouraged. On the other hand, bleeding refers to the cut made in the fish's gills (the equivalent of human lungs). In this case, it can be considered a suitable slaughter method if appropriately done (fast, efficiently and by qualified staff).

Reading about these stunning and slaughter methods, we may think that fish welfare is a new issue. However, a traditional slaughter method, the Japanese ikejime, takes welfare into account by minimising fish suffering. This technique has the disadvantage of being slow (animals are slaughtered one at a time) and requires highly trained staff to carry it out.

Now it's time to talk about laws again

Anything but laws! What a pain! Well, laws are crucial. To make progress in welfare, we need a robust legal framework. As of today, there are no mandatory regulations for farmed fish slaughter. Since 2005, OMSA has published its Aquatic Animal Code, which explains aspects related to welfare during stunning and slaughter. And the draft of the new Guidelines for Sustainable Aquaculture of the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO) refers to welfare, although not specifically.

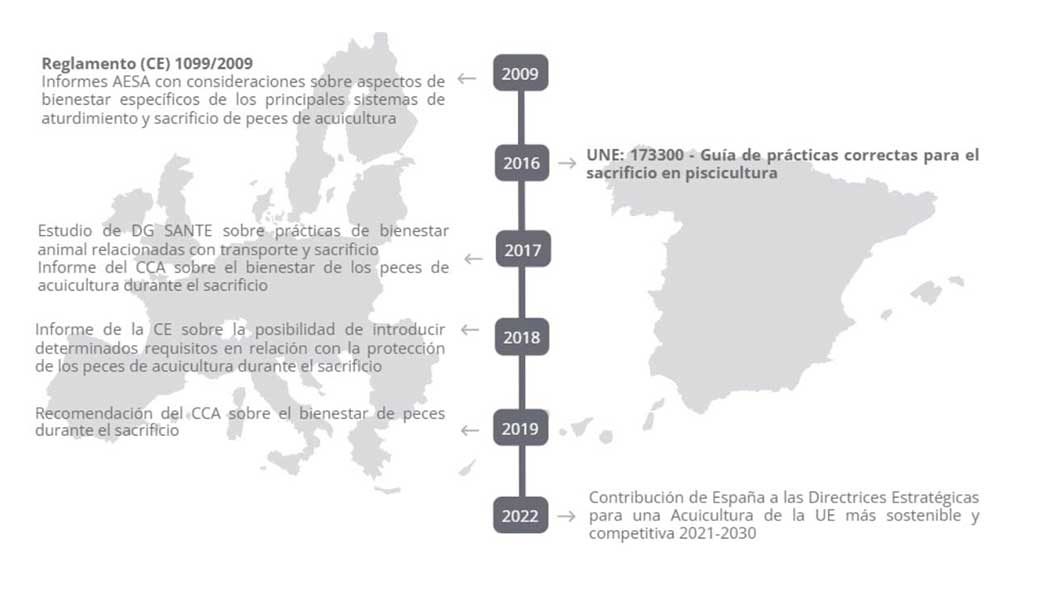

What are the European Union (EU) standards? You can find them in the following timeline, together with Spanish rules (the mandatory ones appear in bold). Apart from Council Regulation (EC) 1099/2009, different European entities have published codes of conduct, scientific reports, studies, recommendations, and other documents discussing farmed fish stunning and slaughter. Sadly, all this effort has yet to be successful. We still need a European law that properly regulates farmed fish slaughter.

From 2021, the EU is reviewing its animal welfare legislation to bring it up to date. Current regulations do not adequately protect farmed fish because they do not include the latest scientific and technological developments related to their welfare. Therefore, as part of the review, the European Commission's Directorate General for Health and Food Safety (DG SANTE) will work on a specific regulation for stunning.

And in Spain?

We have a standard for approved farmed fish stunning and slaughter methods and a plan to develop the sector within the next few years. The problem is that the standard validates methods against animal welfare (e.g., thermal shock), and the plan mentions the need to reduce the fish suffering at slaughter without specifying anything.

In this context, how can we achieve a welfare-inclusive slaughter standard? Firstly, by establishing laws like Norway and the United Kingdom have done. Secondly, Spain has taken an essential step by publishing the first guide on fish welfare in Spanish aquaculture, following the British, Canadian, Chilean, Greek and New Zealand codes of good practices. As the Spanish guide in which Equalia has participated points out, slaughter should be and end as humane as possible, free of pain and suffering for the fish.

What does this certificate mean?

You see them on the labelling when you go to the nearby fish market or supermarket, and you may have doubts like "what exactly do they mean?" or "why are they used?" The answer is straightforward; it is an issue of trust. Trust consumers place in the certificate when choosing one farmed fish over another. Certifications inform about the rearing conditions of the farmed fish we take home, ensuring it has met specific welfare standards and is fit for consumption. Therefore, farmed fish certifications, whose logos are shown below, are another option to assess animal welfare.

But do certification standards really measure animal welfare? Yes and no, like an aquatic version of Schrödinger's cat. Jokes aside, they tend to focus more on food safety and sustainability than welfare. That said, the certifications shown previously are updating their standards to include more specific fish welfare requirements. The new standards will come into effect over the next 3 years.

As an example of these new standards, the table above summarises the stunning and slaughter ones. That is, how slaughter is evaluated in each certificate. At a glance, it can be seen that not all meet the same requirements, with some certificates more aligned with welfare than others. Therefore, it is essential to know what is behind each one to make a more sustainable purchase the next time we go to the supermarket. Because if we unite animal welfare, sustainability, and food safety, we all win, especially the fish.

Related content